Guest Article by Darrell Dow

The last decade has seen the global emergence of nationalism and populism. From Japan to the Indian subcontinent, from the Middle East to Europe and the Americas, the global political divide is increasingly defined by the chasm separating corporate global elites from a rising tide of nationalism expressed via populist means[i].

How should Christians respond to the new wave of nationalism cascading across the globe?

Regrettably, too many Christians, writing about socio-political issues, fail to properly define the terms under discussion. Their analysis frequently devolves to misapplied proof texts and appeals to emotion or rhetorical tropes. The effect, and perhaps the goal, is to theologize and baptize the dogma of the post-WWII liberal consensus.

Regrettably, too many Christians, writing about socio-political issues, fail to properly define the terms under discussion. Their analysis frequently devolves to misapplied proof texts and appeals to emotion or rhetorical tropes. The effect, and perhaps the goal, is to theologize and baptize the dogma of the post-WWII liberal consensus.

In a piece for the Gospel Coalition (TGC), Reformed theologian Michael Horton recently lobbed charges of heresy and blasphemy, calling the “Jericho March” a “sacrilege” with “evangelicals marching on Washington to perpetuate a cult.”

The Jericho March, an ongoing series of public prayer vigils, is an admittedly odd ecumenical assemblage of Catholics, Jews and Protestants, media celebrities such as Alex Jones, and public figures like Michele Bachmann and General Michael Flynn. These small gatherings of religious believers undoubtedly contain some bizarre theology and strained ecumenism alongside dubious claims of private divine revelation. But in the grand scheme of things they are small and relatively inconsequential events.

Nevertheless, the marches have drawn the ire of Christian clergymen and public intellectuals not primarily due to the theological commitments of organizers but because of a connection with the #StopTheSteal effort and the charge that the election was pilfered. Christians seeking to salt the ground in light of Trump’s defeat and vanquish any vestiges of nationalism are working feverishly to undermine the nationalist movement by tying it to odd and extraneous elements in American life rather than the legitimate grievances of Middle America. Horton and his comrades in the Big Eva chorus seem blissfully unaware that we are living through an elite attempt to fully de-Christianize the West.

One can barely conceive of Western Civilization without reference to Christian nations and magistrates adopting a fundamental principle that social order and law are predicated on a belief in God (i.e., Christendom). Horton dismisses Christendom as coercive and incompatible with the Gospel, siding with the Anabaptists rather than Knox, Zwingli, Calvin, and Luther. Horton also assumes that he can deconstruct Christian politics from an apolitical stance. But his arguments have a political impact, leaving the door open to a takeover of the state by anti-Christian forces that use state power to enforce their own set of smelly orthodoxies.

TGC followed up with an even more egregious analysis by Baylor historian Thomas Kidd. Kidd describes nations as “imagined communities” rather than organic, natural, God-created entities. Because he fails to define nationalism, Kidd is unable to explain why it is “bad” and opts instead to offer the unsubstantiated assertion that, “America has long nurtured more problematic forms of Christian nationalism.” He also conflates nationalism with dispensational eschatology and militaristic action designed to bring heaven to earth. Kidd is under the illusion that he is describing Donald Trump and Pat Buchanan. In truth, he paints a picture of George W. Bush and Bill Kristol.

Is “nationalism” an object of idolatry as Horton, Kidd and others claim? Or are nationality and ethnicity an integral part of God’s economy and our piety? In what follows, I will attempt to defend the latter view, sketching a brief apologetic and defense of nationalism based on a theological reading of scripture. Let us begin, then, with a definition of terms.

What is a Nation? What is ‘Nationalism’?

Etymologically, the word nation derives from an Old French term that means “birth, rank; descendants, relatives; country, homeland”. It is directly descended from the Latin (natio) meaning “birth, origin; breed, stock, kind, species; race of people, tribe.” Linguistically, it is connected to the idea of birth–natal, for example, as well as native and nativity are related words.

Many conservative Christians writing about politics attempt to make a distinction between “patriotism” (Good!) and “nationalism” (Bad!). But patriotism is likewise tied to the language of peoplehood. It is derived from the Latin word patria, or fatherland and implies a connectedness to family–to a father (pater). Nation and love of country are intimately tied not merely to a place but to family and people.

Political scientist Francis Lieber writing in the 19th century, offered this definition of the nation:

“The word ‘nation’ in the fullest adaptation of the term, means, in modern times, a numerous and homogeneous population, permanently inhabiting and cultivating a coherent territory, with a well-defined geographic outline, and a name of its own—the inhabitants speaking their own language, having their own literature and common institutions, which distinguish them clearly from other and similar groups of people, being citizens or subjects of a unitary government, however subdivided it may be, and having an organic unity with one another as well as being conscious of a common destiny.”

Anthony Smith, one of the foremost scholars of nationalism, identified six criteria for the formation of the ethnic group, or nation, as:

- A collective identity.

- A common ancestry.

- Shared myths and common historical memories.

- An attachment to a specific territory.

- A shared culture based on common language, religion, traditions, customs, laws, architecture, institutions etc.

- An awareness of ethnicity.

Nations arise organically as extensions of families. People organize themselves into distinct groups for the purpose of living together, serving the broader community, providing a series of collective goods, and securing a posterity. The nation is part of what Edmund Burke called the “eternal society”—the “primeval contract” that provides continuity among the dead, living, and unborn.

Nationalism, while it can morph into a dangerous ideological construct, is best viewed as the means through which the nation is protected and preserved from threats, both internal and external. It is the self-conscious awareness that the nation exists and seeks to develop and improve it, pursuing the codification and securing of the people through government, laws, mores and the building of institutions that make civic life possible.

Nationalism draws much of its power from the idea that members of the nation are part of an extended family, united by ties of blood and soil. But ethnicity and nationality are also somewhat permeable and subjective realities rather than monochrome entities. In the same way that a family can add and enculturate members that do not share a common lineage or language, a nation can do so, too. But as adoption is not normative, neither is the idea of a multicultural or “universal” nation grounded merely upon a common set of ideas or propositions.

What Does the Bible Say?

But does the conception of nations and nationalism offered above have biblical warrant? Like many questions, for the Christian the answer of origins lies in the book of Genesis[ii].

Far from being a product of God’s judgment, national differences and other forms of separation and distinction were baked into the cake of creation, which reflects God himself. The world is spoken into being by a trinitarian God who creates by a process of division. God builds a house.

Scripture begins with these words: “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth.” The Hebrew word used here for God is Elloohiym, which implies divine plurality. The Christian God is trinititarian with three distinct and separate persons sharing the same essence. The Christian God is both one and many, unity and diversity. Though there is one divine essence, attempts to minimize or eradicate distinctions between the persons of the Godhead are blasphemous. Moreover, God creates man in the Imago Dei, the image of God himself. As there are differences within the godhead we expect there to be differences within the created order.

The Spirit of God peered into chaos and darkness, but by his fiat word spoke creation into existence. By a process of separation and division–a form of death–he brought forth life, a process played out throughout scripture with the preeminent example being the death and resurrection of Christ. The multiplicity of creation is a product of divine power, will and sovereignty.

The great variety of stars and planets, plants and trees, fish and birds exist within the unity of a universe. The same holds true of man as God creates two sexes with multiple personalities, colors and nationalities.

God also created family–the genesis of nations themselves–in the Garden. Again, he begins with the process of separation. “So the Lord God caused a deep sleep to fall upon the man, and while he slept took one of his ribs and closed up its place with flesh. And the rib that the Lord God had taken from the man he made into a woman and brought her to the man” (Genesis 2:21-22).

Clearly God’s creation was not uniform and monochromatic but beautiful in its range. In the creation narrative that unfolds in Genesis, the phrase “according to its kind” is repeated. God creates different types of plants and fruit trees. He creates different kinds of sea creatures, birds, and land animals. And he creates male and female.

From the creation of Adam and Eve humanity derives from a common ancestor but diversity springs from that same fountainhead (Acts 17:25-26). In Genesis 1, God gives Adam and Eve a mandate: “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it, and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over every living thing that moves on the earth” (Gen. 1:28). The same task is given to Noah and his sons after the flood (Gen. 9:1, 7). The family is given the task of dominion by God. As God’s vice-regent they incarnate divine image bearers via procreation and spread the glory of God.

But as families grow, they become tribes, clans and nations. The word for “families” shows up repeatedly in Genesis 10, most often translated “clans” (Gen. 10:5, 20, 31, and 10:18, 32). From families, God creates tribes and nations with borders and boundaries separating them. Therefore, according to a biblical definition, nations are in principle just extended families.

The Revolt Against Nations

The Tower of Babel incident recounted in Genesis 11 demonstrates that the desire for a total oneness of humanity—the revolt against divinely appointed and created nationality and ethnicity–stems from pride and rebellion. In verse 4, man attempts to build a city and tower to “make a name for ourselves.”

Genesis 11:5-8 provides God’s response: “And the LORD came down to see the city and the tower, which the children of man had built. And the LORD said, ‘Behold, they are one people, and they have all one language, and this is only the beginning of what they will do. And nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them. Come, let us go down and there confuse their language, so that they may not understand one another’s speech.’ So the LORD dispersed them from there over the face of all the earth, and they left off building the city. Therefore its name was called Babel, because there the LORD confused the language of all the earth. And from there the LORD dispersed them over the face of all the earth.”

It was God who “confuse[d] their language” and “dispersed them from there over the face of all the earth.” National, ethnic, and language groups are not arbitrary human creations or social constructs, but divinely ordained entities that reflect the purposes and glory of God. In the opening chapters of Genesis, and throughout the scriptures culminating in Revelation with the procession of the Kings of Men and their cultural treasures, the bible develops a conception of nationhood defined by a collective identity, common ancestry, shared common historical memories, an attachment to a specific territory, a shared culture based on a common language, religion, traditions, customs and laws as well as an awareness of ethnicity. In short, something very much like ethno-nationalism is taught by scripture.

What Big Eva Says vs. What the Church Has Taught

Yet most of the discussion and commentary from even conservative Christian academics tends to view nationalism with a wary eye. A few examples will have to suffice.

Mark Labberton, president of Fuller Seminary said, “When evangelicals embrace an America-first nationalism, the gospel is co-opted and betrayed.”

Baptist author and “evangelist” Beth Moore recently ascended her Twitter pulpit to call “Trumpism” seductive and dangerous, warning that “Christian Nationalism is not of God.”

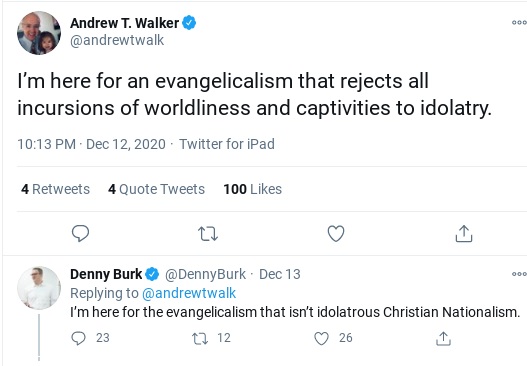

Speaking of the recent “Jericho March,” Southern Baptist Theological Seminary professors Denny Burk and Andrew Walker said the event represented an incursion of worldliness and “idolatrous Christian Nationalism.”

Russell Moore, who claims that Jesus was an illegal immigrant, spent 2016 chiding Southern Baptists from elite media outlets and gloating over the demise of the “white” church, the Christian Right and the historic American nation.

“The wrath of God,” said Moore, is revealed against “Blood and soil”. This is theology by bumper sticker. The rightly ordered love of family (blood) and place (soil) is obedience, not idolatry. Moore also manages to conflate and flatten natural distinctions in his confusion about the nature of the heavenly and earthly kingdoms. “My family includes many Mexican-born immigrants and second- or third-generation Mexican-Americans. My family is the church of Jesus Christ.”

Former George W. Bush speechwriter and Wheaton College graduate Mike Gerson wrote that conservative backers of Donald Trump “are setting the Republican Party at odds with the American story told by Lincoln and King: a nationalism defined by striving toward unifying ideals of freedom and human dignity.”

Here Gerson appeals to a liberal form of civic “nationalism” predicated on a set of abstractions, propositions and “unifying ideals.” This tack is also taken by Albert Mohler, President of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. In an interview, Mohler argues that America is not a nation in the traditional sense defined above, but has a common “creed” or set of ideas that define what it means to be an American. In the creedal or civic definition of American identity, the nation is defined strictly by the principles of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence—the ideals of classical liberalism, the ideals of the “American experiment.”

Mohler says, “I think if we could put together in a room Washington, Hamilton, Jefferson, then fast-forward to Franklin D. Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, and Ronald Reagan, I think that all would absolutely agree upon and insist…that America is a creedal nation. I think if you put all those men in the room, all disparate and diverse as they were, they would be very close in articulating that creed. What has happened to America as a creedal nation?”

Elsewhere, responding tartly to Ann Coulter, Mohler wrote that “toxic” American nationalism, “flies right in the face of the gospel of Jesus Christ and in the command of Christ given in the Great Commission.”

The language employed by these Christians is historically new, primarily a phenomenon of the post-Civil Rights era. Prior generations of Christians spoke of the value of nations and also couched their discussion within a web of obligations and duties–a this-worldly piety.

Geerhardus Vos, for example, wrote, “Nationalism, within proper limits, has the divine sanction; an imperialism that would, in the interest of one people, obliterate all lines of distinction is everywhere condemned as contrary to the divine will.” And these differences require a relative measure of separation. “Under the providence of God each race or nation has a positive purpose to serve, fulfillment of which depends on relative seclusion from others.”[iii]

“Nations,” wrote Alexander Solzhenitsyn, “are the wealth of humanity, its generalized personalities. The least among them has its own special colors, and harbors within itself a special aspect of God’s design.”[iv]

Moreover, men are born into a social order that sustains and nourishes them and owes a debt of gratitude not just to God, but also to parents, kinfolk, and people.

“Piety must begin at home as well as charity,”[v] wrote Baptist Charles Spurgeon. “The highest degrees of divine affection must not divest us of natural affection,”[vi] wrote Puritan Matthew Henry.

“The Hebrew Scriptures do indeed say enough, as in the text, to justify an intense love of native land and its institutions,” wrote Southern Presbyterian R. L. Dabney. “The aggregation of men into separate nations is therefore necessary; and the authority of the governments instituted over them, to maintain internal order and external defence against aggression, is of divine appointment. Hence, to sustain our government with heart and hand is not only made by God our privilege, but our duty.”[vii]

“Man is a debtor chiefly to his parents and his country, after God,” wrote Thomas Aquinas. “Wherefore just as it belongs to religion to give worship to God, so does it belong to piety, in the second place, to give worship to one’s parents and one’s country [i.e., one’s people]. The worship due to our parents includes the worship given to all our kindred, since our kinfolk are those who descend from the same parents.”[viii]

Most Christians once understood these obligations and grasped that the cultivation of natural duties preceded the pursuit of supernatural virtues.

Many Christians also fear that nationalism impedes the proclamation and spread of the gospel. But as I have shown, scripture assumes nations as divine creations that serve the purpose of aiding man: “He made from one man every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth, having determined allotted periods and the boundaries of their dwelling place, that they should seek God, and perhaps feel their way toward him and find him” (Acts 17:26-27). Nature and nations are not flattened or destroyed by the gospel, but restored and perfected by it. Moreover, Christ himself commands his people to disciple nations as nations, not merely as individuals: “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you” (Matt. 28:19-20).

Nationalism is not thus hostile to the gospel. In order to build a righteous nation or disciple a nation, there must first be a nation! Nationalism is normative and good—don’t let any priest, prelate, pastor or professor tell you otherwise.

____________

Darrell Dow writes from Crestwood, Kentucky. He is the co-author of Who Is My Neighbor?: An Anthology In Natural Relations. His work has appeared in Chronicles: A Magazine of American Culture, Antiwar.com, and The American Remnant.

We are starting a Fight Laugh Feast quarterly print magazine! Click HERE to subscribe.

End Notes:

[i] Populism is not the main topic of this essay but is generally the means through which “Nationalism” is conveyed politically at the present time. These movements can take a variety of forms. Populism is not a mere style of politics, but for our purposes consists of three core ingredients:

1) an attempt to make the popular will heard and acted on;

2) the call to defend the interests of the plain, ordinary people; and

3) the desire to replace corrupt and distant elites

[ii] The New Testament writers likewise ground their anthropology in the early chapters of Genesis (Matthew 19:4-5, I Timothy 2:13-14, I Corinthians 11:8-9, I Corinthians 11:14-15, etc.). Creation is made good and grace does not flatten nature but restores and perfects it.

[iii] Vos, Biblical Theology, p. 60

[iv] Solzhenitsyn, Alexander, Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech

[v] Spurgeon, Charles, Words of Counsel for Christian Workers, pp. 5-6

[vi] Henry, Matthew, Commentary on Genesis 24:29-53

[vii] Dabney, Robert Lewis, Sermon: The Christian Soldier

[viii] Aquinas, Thomas, Summa Theologiae, Second Part of the Second Part, Question 101